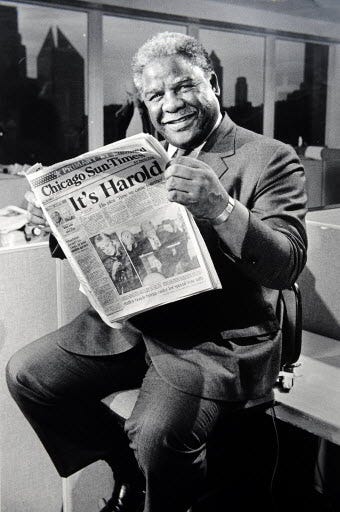

Celebrating Harold's 100th birthday

Chicago first Black mayor led the great reform movement at CPS

Chicago's great mayor, Harold Washington would have turned 100 years old today. More than a mayor, Harold was a community leader and organizer whose election was the culmination of a struggle rooted in the ‘60s freedom movement.

In 1983, Harold made history in two ways. He became Chicago's first African-American mayor and the first whose election grew directly from a high tide of Black resistance to racist machine rule. That movement was joined by a grassroots coalition of progressive forces citywide. During his first term, a racist cabal of 29 white aldermen, led by the two Eddies, Vrdolyak and Burke, blocked his every move in the City Council. However, by 1987, when Washington won re-election, court-ordered reapportionment of wards led to the election of some allied Latino aldermen, and the mayor gained some breathing room.

At that time, the public schools, the most racially segregated in the nation, were in a state of deep crisis. Badly underfunded by Republicans in Springfield, who referred to CPS as "a black hole," and ruled by a self-perpetuating top-heavy bureaucracy, Chicago's school system was the picture of abject failure. Chicago-hating Pres. Ronald Reagan went so far as to send his racist Sec. of Education William Bennett to the city to denounce CPS as the "nation's worst" school system.

In the wake of the record 19-day teachers' strike (Sept. 8 to Oct. 2), angry and frustrated parents raised their demand for sweeping change. While the mayor met separately with the two sides in the strike, urging reconciliation, he refused to get involved directly in the talks or to dictate terms of a settlement.

''Everyone says I was not involved, but you solve problems through discussions,'' he said. ''I had some of our best people working on the problem. There was a constant quest on my part to resolve the strike.'' -- NY Times

The five-week shutdown, which became the longest teacher strike in city history, and the third during Washington's tenure, concluded with a tentative agreement of a two-year contract that the CTU membership ratified the following day. The new contract mandated a 4% pay increase the first year, followed by another 4% the second year, "if adequate funds could be found," and a reduction in class sizes by two students in grades K-3. But since neither side had a plan for generating new revenue, the raises came at the expense of the firing of 1,700 teachers, low-level administrators, and staff.

However, change was in the air, thanks to a resurgence of a powerful reform movement of CPS parents and community activists. Washington had been working behind closed doors on a plan to overhaul the school district. When the teachers’ strike hit, he seized on the political unrest and anger in the black community to make a public commitment to school reform.

He announced plans for an education summit that would search for a path forward that included all stakeholders. The Summit, held at UIC (Circle Campus) was attended by more than a thousand participants. Washington died of a heart attack before the summit could carry out its work, but the momentum for change remained alive.

It's important to note that at the time, Black leadership of the school system was apparent. The city's mayor, school board chief, superintendent, and teachers' union president were all African-Americans.

The sweeping changes that followed were marked by a shift in power from the top of the bureaucratic machinery down to the local school level, including the creation of parent/community-dominated Local School Councils (LSCs). While the victories were short-lived and later reversed completely during the next Mayor Daley's regime, they still showed what is possible through grassroots community organizing.